Kiyoko’s Story

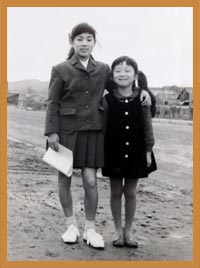

Kiyoko Ishiyama’s family owned the Japanese house that was given to Boston. Kiyoko did not actually live in our Japanese House, but her aunt and uncle did and she visited them often. Her own home was also a machiya-style home, very similar to ours, with a shop in the front and a living area in the back. Today, Kiyoko is a master Japanese calligrapher and watercolor painter. Through her art, she shares her memories of growing up in the 1940s and 50s in a machiya in the Nishijin neighborhood where our Kyo no Machiya came from. Scroll down for her story.

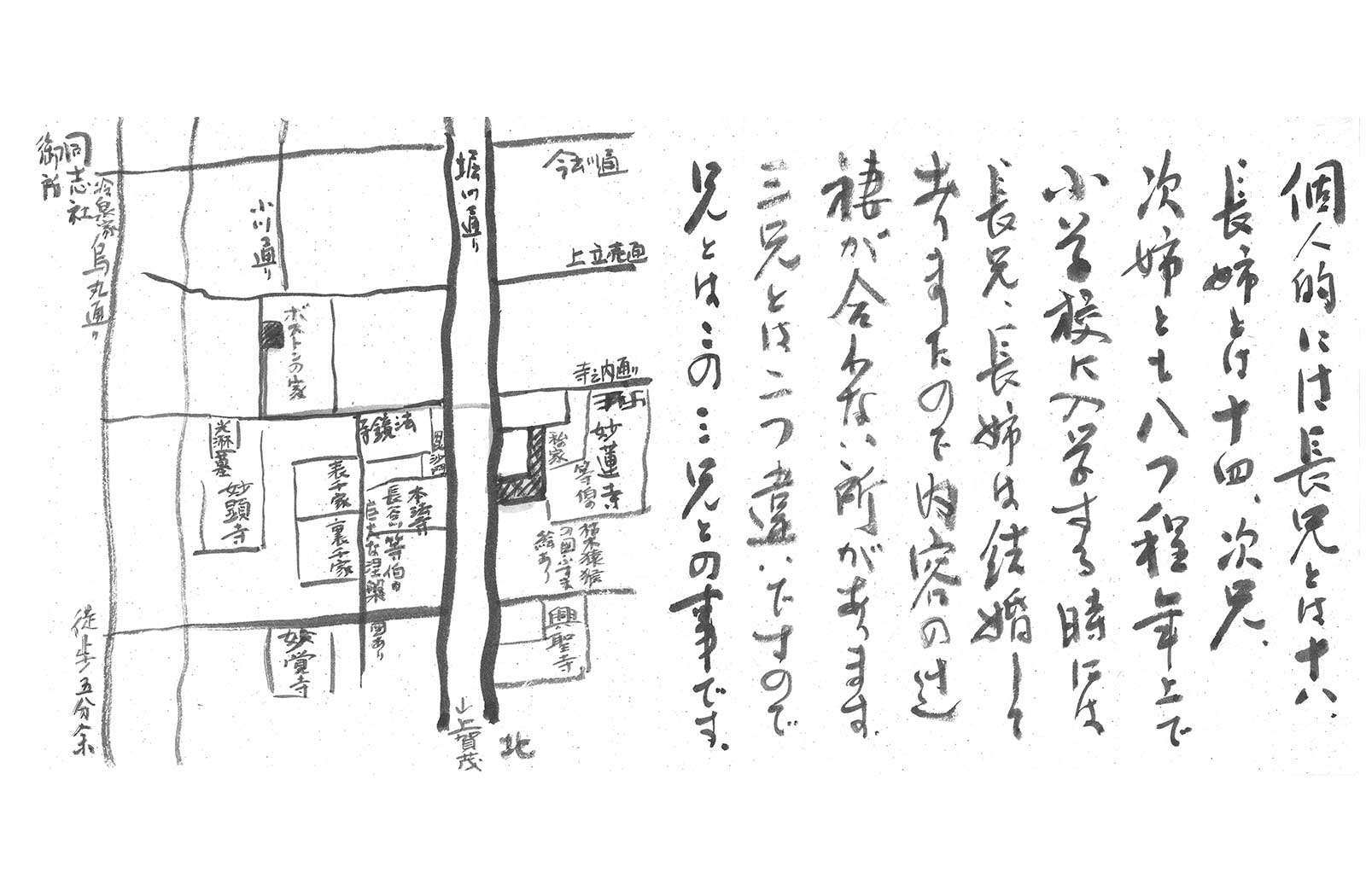

My Neighborhood, Nishijin

As a child in the 1940s and 50s, I lived near my aunt and uncle who lived in the machiya that is in Boston Children’s Museum today. We lived in Kyoto’s famous Nishijin silk weaving area. While walking in our neighborhood, I remember hearing the sounds of the silk looms — “gacchan gacchan” — coming from many homes.

Kyoto’s Nishijin District is known for its silk and textile industry. The history of Nishijin weaving dates back to the Heian period of Japan (794-1192). This type of silk fabric is used for making beautiful traditional garments like kimono and obi.

My Mother in the Kitchen

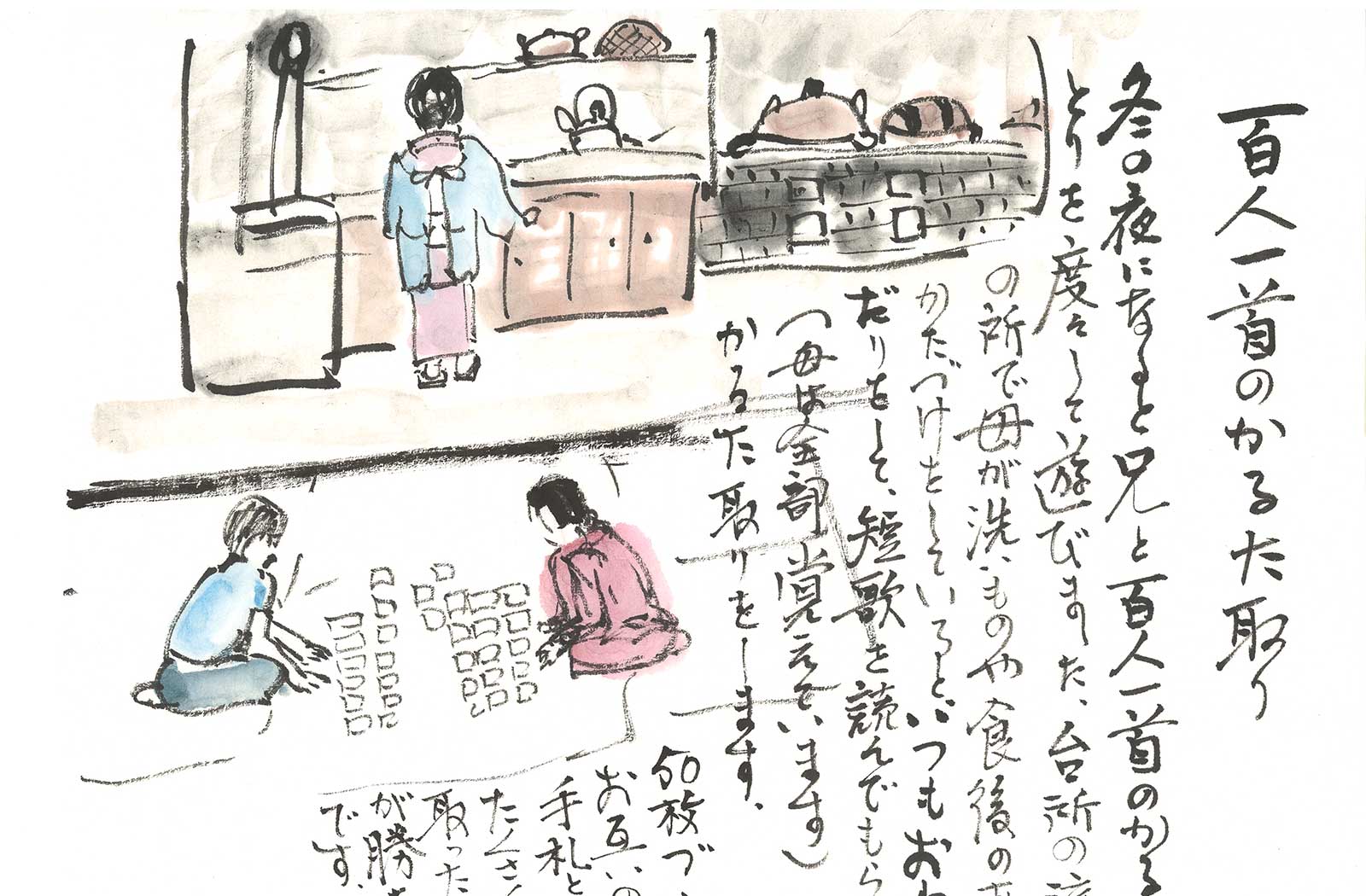

Our kitchen had earthen floors and a well where my mother used a bucket and a pulley to draw up water. She cooked on a wood-burning stove. We liked to think that the Hotei statues, the kitchen guardians, protected our family from fire. When we stepped up into the dining room next to the kitchen, we took off our shoes. I remember playing card games with my brother in the dining room while our mother cooked in the kitchen. During long winter nights, our mother would play with us by reciting the beautiful old poems she had memorized as a child, while we listened and tried to match the poems to the cards.

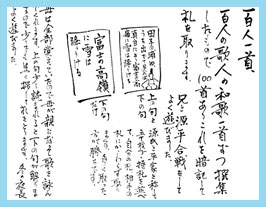

Karuta is a popular card game, especially winter time. One variation is Hyakunin Isshu, the “Game of 100 people, 100 poems.” It is a set of 100 Japanese waka poems, each written by different poet and printed on a separate card. Memorizing all 100 poems is a big advantage.

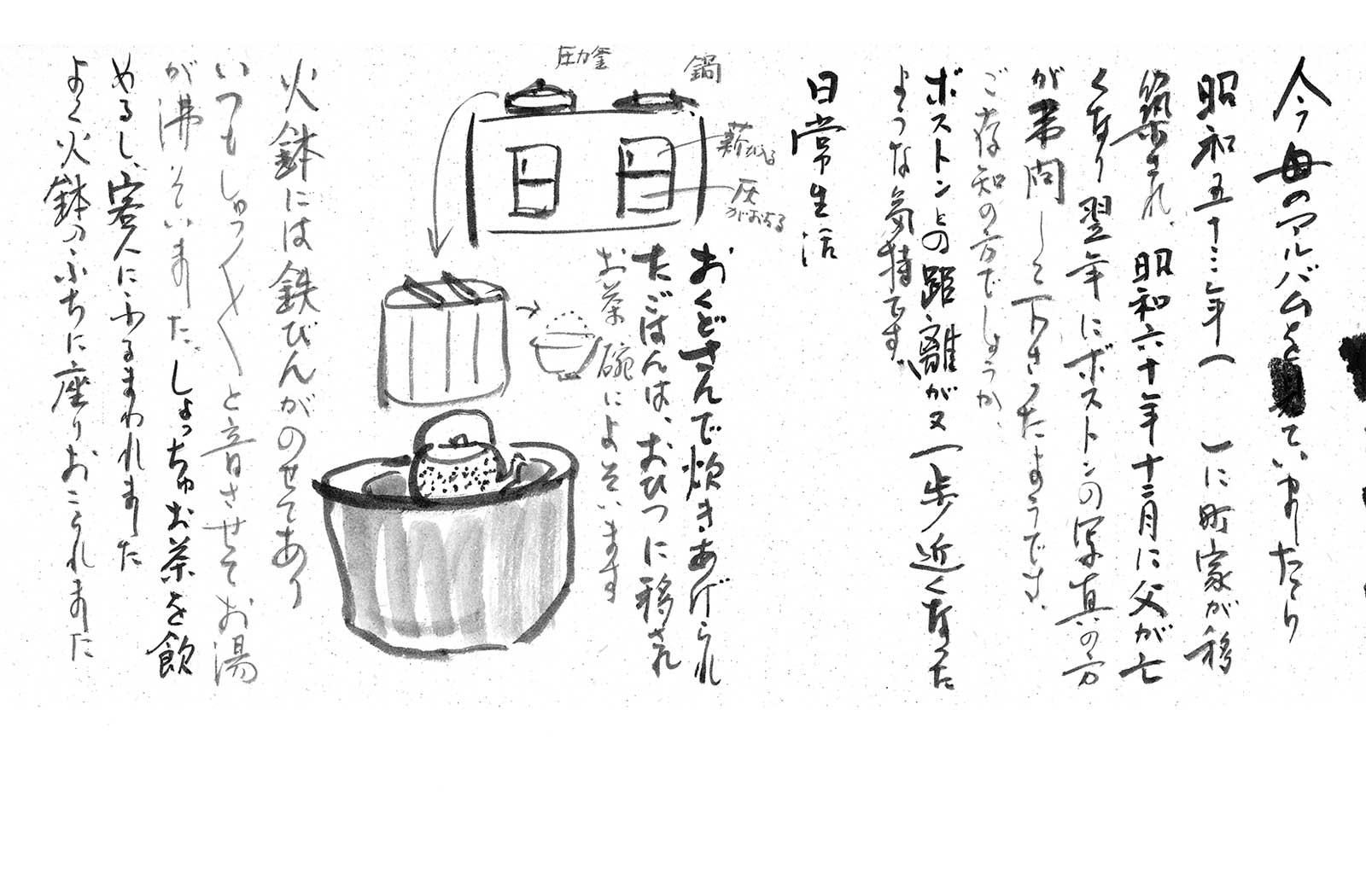

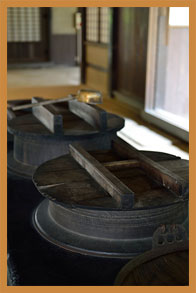

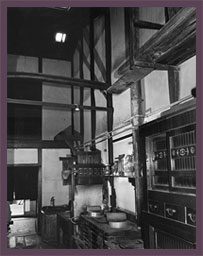

Okudo-san and Hibachi stove

Kitchens in Kyoto’s machiya houses were so important to the family that we called them Okudo-san, which literally means “Mr. Cooking Stove,” almost as if it were a member of the family. All the most important things came from the wood-burning stove, especially rice and tea!

The rice cooked in the kitchen is moved to the wooden container to carry into the dining room, and then served into rice bowls at the table. There was no electric rice cooker, so rice was cooked in a metal pot, called okama, on the brick stove, or Okudo-san.

Let’s Eat – Itadakimasu!

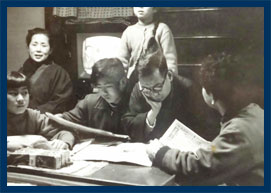

Since our house also served as our father’s silk business workspace, workers and products filled our home during the daytime. There was almost no privacy or no play area for me. Yet, somehow by nighttime, everything was cleaned up and cleared away, and my family again had a private, cozy family space. Our dining table was a traditional low table, so we sat on the floor around the table instead of in chairs.

Tokonoma

I remember my parents enjoying various arts. My father loved art and history museums. He often took my siblings and me to the museums. My mother was a gardener and enjoyed flowers a lot. She had beautiful roses planted in her garden and often gave them away as gifts to the neighbors as they walked by.

In Japanese houses, the formal room where family guests are entertained often has a tokonoma and a garden view. The Tokonoma is used to display formal flower arrangements, seasonal scrolls, or other seasonal objects. Guests are often served tea and Japanese wagashi sweets in very special way.

Heated Kotatsu Table

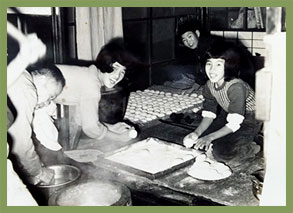

Machiya are very drafty, and this made us feel that Kyoto winters were bone-chilling. Kyoto is in a basin surrounded by mountains and hills. During the winter, the cold wind blows down from the hills. Occasionally it snows in Kyoto. Perhaps because winter is cold, we had many family celebrations during the winter to warm the spirit. The Oshogatsu New Year’s celebration was my favorite. Families and relatives gathered in my home to celebrate together. We pounded rice to make mochi — the special holiday treat — listened to the temple bells on New Year’s Eve, and then visited Imamiya Shrine on New Year’s Day.

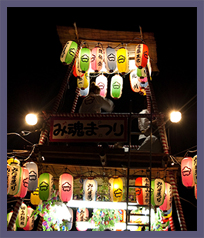

Summer Night

To stay cool in the summertime, we simply relied on the flow of breezes in the house. We stored away the sliding partitions between the rooms, and replaced them with light bamboo blinds called sudare. Having a garden was very important for cooling. My chore was uchimizu — sprinkling water on the garden and street. This would cool down the area, and create more airflow.

Kyoto has a humid subtropical climate and is known for its very hot and humid summers. Machiya house are specially designed for surviving the long and uncomfortable summers.

Kyoyasai

Although Kyoto is a city, it is also known for agriculture, which produces the world famous Kyoto cuisine. Vegetables grown in Kyoto are so special that they even have their own name — Kyoyasai — which means vegetables of Kyoto. They are tasty whether eaten raw, cooked or pickled.

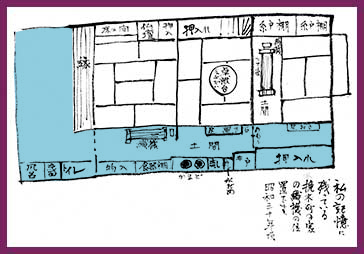

In the 1940s and 50s, all machiya houses were laid out in similar ways. They were kept very clean, with the kitchen, toilet, bath and garden all very well-placed around the "outside" (indicated by the shaded area in the diagram). We took off our shoes to step up into the "inside" living area.

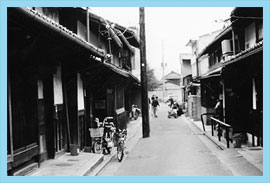

Kamishibai man with bicycle

The neighborhood streets were used for getting together with friends and playing. The kamishibai man came by often to tell his stories from his special bicycle. He always stopped his story right at the most thrilling point so that we would come out again when he returned. My friends and I looked forward to hearing the conclusion of the story, and eating the candy he sold!

My neighborhood as a playground

My friends and I often played games near the temples in our neighborhood.

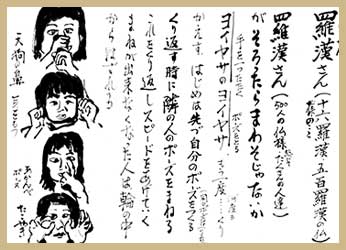

Rakan is the Japanese Buddhist term for arhat, or person who has achieved nirvana, or enlightenment. Rakan is also used in a popular children’s game we used to play. In the game, a player chants the following: "Once Rakan-san comes together, let’s pass around, pass around!" then makes a silly face. Typical faces that we made are called: Tengu's Nose, Grabbing the Ears, Opening Eye Pose, and Fried Octopus.

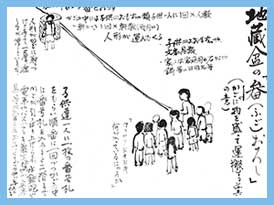

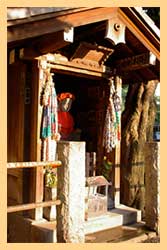

O-Jizo sama

Jizo is considered a guardian of children, women, and travelers. He is one of the most beloved Buddhist figures in Japan. Stone statues of Jizo are a common sight on many street corners of Japan. In Kyoto, almost every neighborhood and street block has its own Jizo statue. Everyone celebrates the Jizo-bon festival in the summer.

After the Jizo-bon ceremony, it was usually the time for Fugo-oroshi event. Fugo is a basket, and oroshi means taking down. Therefore, fugo-oroshi is an action of taking down a basket. A handmade zip line was placed between the second floor window of a machiya and the street, and a basket with gifts inside was slid down the line to receivers on the street. It is fun for kids and adults alike. The basket usually contained toys for kids and household items for adults.

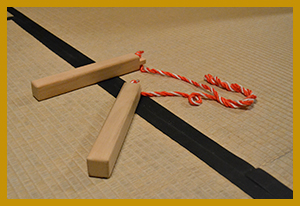

Fire prevention walks

We always feared fire. Machiya were made of wood, paper, and straw, and built very close together. If a fire started, it could quickly spread throughout the whole neighborhood and city. All our neighbors reminded each other to extinguish the fire at night. Even the children went on fire prevention walks at night. We thought that was a great fun in the evening, even though the purpose was very serious.

We are deeply grateful to Kiyoko for sharing her personal memories in such a vivid, artistic and

evocative way. She has brought the story of our treasured Kyo no Machiya to life in a way we could not

have imagined. We are also thankful to Setsuko and Frank for connecting us with Kiyoko.